Ride Together, Ride Better: The Art of Synchronized Touring

Group riding is the heartbeat of the motorcycling community—a blend of shared adventure, increased visibility, and the safety of “having each other’s backs.” However, a group is only as safe as its least disciplined rider. To master the art of synchronized touring, you must transition from a solo mindset to a “unit” mindset, where every lane change and braking maneuver is executed with the entire pack in mind.

1. The Anatomy of a Successful Pack

A well-organized group doesn’t just ride; it operates with a clear hierarchy:

- The Lead (Road Captain): Usually the most experienced rider. They set the pace, navigate, and signal hazards first. They are responsible for the group’s safety and flow.

- The Sweep (Tail Gunner): Rides at the absolute back. They monitor the group for mechanical issues or riders falling behind. They are typically equipped with a first-aid kit and tools.

- The Beginner’s Slot: If you are new, position yourself directly behind the Lead (second in line). This allows the Lead to monitor your pace in their mirrors and protects you from the “slingshot effect” (where riders at the back have to speed up and slow down aggressively to keep up).

2. The Formation: Staggered vs. Single File

- Staggered Formation: The standard for open roads. The Lead rides in the left third of the lane, the second rider in the right third, and so on. This keeps the group compact while giving everyone a clear “escape path” to their side.

- Single File: Switch to this on narrow, curvy roads or through construction zones. Increase your following distance to 2–3 seconds to allow for independent cornering lines.

3. Essential Hand Signals (The Silent Language)

Since you can’t always hear each other, these universal 2026 signals are vital:

- Hazard on Road: Point with your left hand (if on the left) or shake your right foot (if on the right) toward the debris/pothole.

- Single File: Raise your left arm with one finger extended.

- Slow Down: Extend your left arm out, palm down, and move it in a “patting” motion.

- Fuel Stop: Point or tap your fuel tank with your left hand.

4. The “Rubber Band” Effect

Groups naturally stretch and compress. To minimize this:

- Don’t “Target Fixate”: Look past the rider in front of you. If you only watch their brake light, you will react too late.

- Smooth Inputs: Avoid sudden “panic braking.” If the Lead slows down, ease off your throttle early to give the riders behind you a gradual warning.

Here’s your go-to guide for mastering group riding etiquette.

1. Riding Formations: Precision in Motion

Formations are the “social distancing” of the motorcycling world. They ensure every rider has a dedicated space cushion to react to hazards without colliding with their teammates. By switching between Staggered and Single File patterns based on the terrain, your group maintains a professional, predictable, and safe presence on the road.

1. The Staggered Formation (Your Highway Standard)

This is the default for multi-lane highways and wide, open roads.

Compact Length: It keeps the group tighter than a long single line, making it easier for cars to pass the entire group at once.

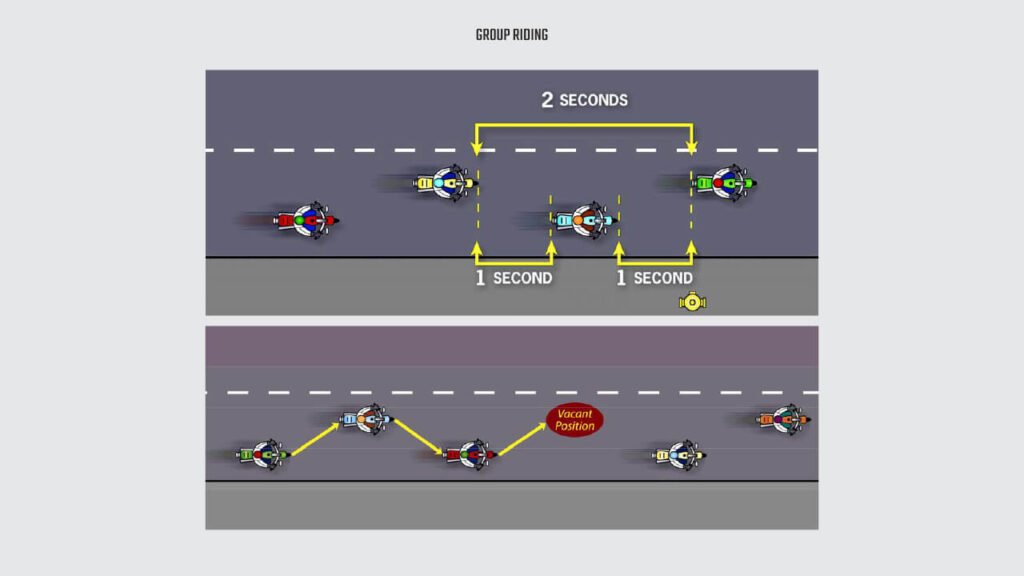

The Pattern: The Lead Rider takes the left-third of the lane. The Second Rider follows about 1 second behind in the right-third. The Third Rider is 2 seconds behind the Lead in the left-third, and so on.

Why it works:

Enhanced Visibility: Each rider can see past the person directly in front of them, providing a clear view of oncoming traffic and road debris.

The Escape Path: If a car suddenly swerves into the lane, you have the entire width of the lane (left or right) to move without hitting another bike.

2. The Danger of “Side-by-Side” Riding

You may see “parade style” riding in movies, but in reality, it is extremely dangerous:

- Zero Maneuverability: If you hit a pothole or a patch of gravel, you have nowhere to swerve because your teammate is occupying your escape space.

- Handlebar Tangling: Even a slight gust of wind or a momentary lapse in concentration can cause handlebars to touch, leading to a catastrophic multi-bike crash.

3. When to Switch to Single File

The Lead Rider will signal (usually one finger held high) to transition into a straight line for technical or congested sections:

- Curvy Roads & Switchbacks: You need the full width of the lane to choose the safest “line” through a corner.

- Narrow Bridges & Construction Zones: Where the lane width is restricted.

- Off-Road & Water Crossings: Where you must follow the exact tracks of the rider ahead to avoid hidden rocks or deep mud.

- Steep Descents: In Ladakh, engine braking is vital; single file gives you a 3-second buffer in case the rider ahead stalls or brakes suddenly.

Pro-Tip: The “Gap Closure” Rule

If a rider in the middle of a staggered formation leaves the group, do not accelerate past the rider in front of you to fill the gap. Instead, the group should “cycle up”—the rider behind the empty spot moves to the opposite side of the lane, and everyone behind them follows suit. This keeps the formation intact without risky mid-lane overtaking.

2. Know Your Role: The “Chain of Command” in a Pack

A group ride is not a collection of individuals; it is a single unit moving through traffic. To function safely, every rider must understand their specific responsibilities. By 2026, the roles of the Road Captain, Marshal, and Sweep have become standardized to ensure that even in the most chaotic mountain terrain, the group remains connected and disciplined.

1. The Key Leadership Roles

The Road Captain (Lead Rider)

The “General” of the ride. They sit at the very front and carry the heaviest mental load.

- Responsibilities: Navigating the route, setting a consistent pace (accounting for the “slinky effect” at the back), and signaling hazards first.

- The 2026 Mindset: They don’t just ride for themselves; they ride for the entire group’s line of sight.

The Marshal (The Enforcer)

Usually positioned in the middle or roaming the flank of the group.

- Responsibilities: They act as the “police” of the formation. They ensure riders maintain a proper staggered gap and assist with traffic control at complex intersections (where legal) to keep the pack from being split by cars.

The Sweep (Tail Gunner)

The “Guardian” at the absolute rear. This is arguably the most difficult role.

- Responsibilities: They monitor the entire group from behind. If a rider breaks down or crashes, the Sweep pulls over with them while the rest of the group proceeds to a safe designated regrouping point.

- The 2026 Tech: The Sweep is usually the rider with the best communication gear (Sena/BluArmor/V6 Pro) and the most comprehensive first-aid and tool kit.

2. The Middle Riders: The Strength of the Pack

Even if you aren’t in a leadership role, you are a critical link in the chain:

- The Relay: Your primary job is to pass hand signals from the Lead back to the Sweep. If the Lead signals a “pothole left,” you must repeat it for the rider behind you.

- Gap Management: You are responsible for maintaining the “1-second staggered” or “2-second single file” distance. If you leave too much space, cars will cut into the formation; too little, and you lose your braking cushion.

3. Essential Advice for Beginners

If this is your first tour or your first time riding in a large pack:

- Avoid Lead or Sweep: These roles require high “situational awareness”—the ability to ride while simultaneously managing 10 other people.

- The “Safety Slot”: Ask to be placed in the second or third position (right behind the Road Captain).

- Why? You don’t have to worry about navigation, the pace is most stable at the front, and the most experienced rider (the Lead) can keep a constant eye on you in their mirrors to see if you are struggling.

The 2026 “No Hero” Rule

In modern group riding, it is a sign of maturity, not weakness, to admit you are tired or that the pace is too fast. If you feel overwhelmed, signal your Marshal or the Lead at the next stop. A good group will always adjust its speed to match the least experienced rider, ensuring everyone reaches the destination in one piece.

3. Maintain a Consistent Pace

Rhythm is the “glue” that holds a group together. A consistent pace reduces the “Rubber Band Effect”—where small speed changes at the front become massive, dangerous surges and braking at the back. By riding at a steady, predictable speed, you ensure the entire pack moves as a single, fluid unit.

Understanding the Rhythm

- The Slinky Effect: When the lead rider brakes even slightly, riders at the back often have to brake much harder to avoid a collision. Conversely, when the lead speeds up, the tail has to “race” to catch up. To stop this, every rider must avoid sudden throttle or brake inputs.

- Eyes Up (The 4-Second Rule): Don’t just watch the taillight of the bike directly in front of you. Look 3–4 bikes ahead. This allows you to anticipate traffic or speed changes early, letting you ease off the throttle rather than stabbing at the brakes.

- Uniform Speed: Unless you are changing formation, try to keep your speedometer steady. If the group has agreed on 80 km/h, stay there. Constantly fluctuating by ±5 km/h forces everyone behind you to work twice as hard to maintain their gap.

What to Do If You Fall Behind

It happens—a red light splits the group, or a slower vehicle gets between you and the pack.

- Don’t Panic: Never “ride over your head” (exceeding your skill or safety limits) to catch up. A panic-driven rider is a danger to themselves and others.

- Trust the Plan: A professional group will have a “Regrouping Protocol” (discussed in the pre-ride meeting). Usually, the Lead will slow down or pull over at a safe, pre-designated landmark to wait for you.

- The “Wait at the Turn” Rule: In 2026, the standard rule is: If the group makes a turn, the rider in front of the gap waits at that intersection until they see the following rider. As long as you keep going straight, you won’t get lost.

Pro-Tip: The “Mirror Check” Chain

You are responsible for the person behind you. Periodically check your mirrors; if you don’t see the rider behind you, slow down. If the entire group follows this “look back” chain, the Lead will eventually notice the slowdown and adjust the pace, keeping the group together naturally.

4. Master the Silent Language: Essential Hand Signals

When the roar of the wind and the hum of engines make verbal communication impossible, hand signals become your group’s nervous system. Clear, deliberate signaling allows information to flow from the Lead to the Sweep in seconds. In 2026, even with the rise of Bluetooth intercoms, these physical cues remain the most reliable “fail-safe” for group coordination.

The Universal Signal Library

To ensure everyone is on the same page, the Road Captain should conduct a physical demonstration of these signals during the pre-ride briefing.

- ✋ Palm Down, Moving Up and Down (Slow Down): Use this when approaching a village, a sharp curve, or a sudden change in road quality. It warns the riders behind to start engine braking rather than slamming on the brakes.

- ✊ Fist Raised High (Stop): This is an immediate command to prepare for a full halt. The signal should be passed back rapidly so the Sweep knows the group is stopping.

- 👉 Pointing to the Fuel Tank (Refuel Needed): A vital signal in the high-altitude desert. If any rider hits their “reserve,” they should move to the side of the formation and point to their tank to alert the Marshal or Lead.

- ✌️ Two Fingers in the Air (Formation Change): This tells the group to move into Staggered Formation. (Conversely, one finger indicates a move to Single File).

- 🫳 Pointing Downward (Hazard Ahead): Point specifically toward the ground on the side where the hazard is (pothole, gravel, or “pagal nalla”). If the hazard is large, some riders prefer to shake their foot on the side of the danger.

Pro-Tips for Effective Communication

- The “Relay” Responsibility: It is not enough for the Lead to signal; every rider in the pack must repeat the signal. This ensures that the riders at the very back (who cannot see the Lead) receive the information in real-time.

- Be Distinct: Don’t make lazy or “small” gestures. Use your whole arm so the rider behind you can see the signal clearly in their mirrors or through the dust.

- Safety First: Only signal when it is safe to take your hand off the handlebar. If you are in the middle of a technical turn or a deep gravel patch, prioritize control over signaling.

- Intercom Integration: If your group uses Bluetooth headsets (like Sena or Cardo), use the voice channel to explain the signal. (e.g., “Slowing down for sheep on the road”).

5. The Pre-Ride Briefing: Your Mission Blueprint

A group ride without a briefing is just a collection of strangers riding in the same direction. The Pre-Ride Briefing is where a group of individuals becomes a team. It’s the final 10 minutes spent on the ground that ensures the next 10 hours on the road are safe, coordinated, and stress-free.

The Essential Briefing Agenda

A professional 2026 briefing should cover these four critical pillars:

1. The Route & The “Re-Group” Points

- The Path: Don’t just rely on GPS. Briefly describe the terrain (e.g., “The first 50 km is smooth tarmac, followed by 20 km of gravel and three water crossings”).

- The Stops: Identify specific landmarks for fuel and food.

- The “Lost” Protocol: Clearly state the plan if the group gets split. (“If you lose us, stop at the next major T-junction and wait. Do not guess the direction.”)

2. Role Assignment & Accountability

- The Leaders: Formally introduce the Lead (Road Captain) and the Sweep.

- The “Medic”: Identify who is carrying the primary first-aid kit.

- The Mechanic: Designate the rider with the most tools and technical knowledge. Everyone should know who to signal first if they hear a strange noise from their engine.

3. Emergency & Contact Sync

- The List: Exchange or verify that everyone is on the group’s WhatsApp or Telegram thread.

- ICE (In Case of Emergency): Ensure the Lead and Sweep have a list of everyone’s blood group and emergency contact numbers. In remote areas like Sarchu, this information is a literal lifesaver.

4. Signal Standardization

- Even if you think everyone knows the signals, do a 60-second live demonstration.

- Show the signals for “Single File,” “Hazard,” and “Fuel” to ensure there is no “regional dialect” confusion between different riders.

The “Tech Check”

Before putting on helmets, perform a 30-second light check. Have everyone turn on their ignition and test:

- Brake Lights: So the person behind you knows when you’re slowing.

- Indicators: Essential for synchronized lane changes.

- Intercoms: If using Mesh or Bluetooth, pair all devices now. Trying to pair mid-ride leads to distracted riding and accidents.

6. Stay Connected: The Communication Matrix

While the roar of the Himalayan wind can isolate you, modern technology ensures the group remains a cohesive unit. In 2026, we utilize a multi-layered communication strategy—ranging from real-time voice mesh to low-bandwidth emergency apps—to bridge the gap between riders. However, tech is a supplement, not a replacement; your eyes and hands remain your primary tools for safety.

The 2026 Connectivity Toolkit

1. Bluetooth & Mesh Intercoms (Real-Time Coordination)

For the Lead, Marshal, and Sweep, a Mesh Intercom (like Cardo or Sena) is essential. Unlike standard Bluetooth, Mesh technology allows riders to drop in and out of the connection automatically as they move, which is perfect for winding mountain roads.

- The Benefit: Instant warnings about oncoming trucks around blind hairpins or immediate calls for a “mechanical stop.”

- The Protocol: Keep the “chatter” to a minimum. Use the channel for navigation and safety alerts so the “audio airwaves” remain clear for emergencies.

2. Group Apps (Location & Logistics)

- WhatsApp/Telegram: Best for sharing live locations during lunch breaks or sending “All Safe” updates once you reach a guesthouse with Wi-Fi.

- Zello (Push-to-Talk): This app turns your smartphone into a walkie-talkie. It works remarkably well on low-bandwidth 2G/3G signals often found in remote Ladakhi villages.

3. Walkie-Talkies (The Heavy Duty Backup)

If your expedition includes a Support Vehicle (backup SUV carrying luggage/fuel), high-frequency walkie-talkies are a must. They have a longer range than Bluetooth and allow the driver to alert the riders about upcoming road blocks or fuel shortages.

The “Tech Trap” Warning

Technology in the Himalayas is famously fickle. Batteries drain faster in the cold, and “dead zones” are frequent. To ensure you aren’t left stranded when the signal drops:

- Visual Signals First: Always assume the intercom has failed. Execute your hand signals as if no one can hear you.

- Offline Maps: Ensure every rider has downloaded the entire Ladakh region on Google Maps or Organic Maps for offline GPS use.

- Battery Management: Carry a high-capacity power bank in your tank bag to keep your phone and intercom charged during long 10-hour riding days.

Pro-Tip: The “Tail-Light Check”

In 2026, many riders use satellite communicators (like Garmin inReach) for extreme off-road stretches (like the route to Umling La). If you don’t have one, stick to the “Mirror Rule”: If you can’t see the headlight of the rider behind you for more than 30 seconds, slow down or stop. This manual “analog” communication is the only 100% fail-safe method in the mountains.

7. The “No Lone Wolf” Policy: Unity Over Ego

The moment you join a group formation, you surrender your identity as a solo rider to become part of a larger, moving organism. In the high-stakes environment of the Himalayas, “Lone Wolf” behavior is more than just annoying—it’s a safety hazard that puts everyone at risk. Group touring is a test of discipline, not a showcase for individual ego.

Dangerous Habits to Leave Behind

To maintain the safety and rhythm of the pack, strictly avoid these four disruptive behaviors:

1. Overtaking Within the Formation

- The Danger: Moving up the ranks within your own lane creates confusion. The rider you are passing might need to swerve to avoid a pothole, unaware that you are in their blind spot.

- The Rule: Stay in your assigned slot. if you absolutely must change positions, do it only during a scheduled stop or signal the Marshal to facilitate a safe pass.

2. The “Ghost” Exit (Leaving without Informing)

- The Danger: If you peel off to take a photo or explore a side trail without telling the Sweep or Lead, the entire group will eventually stop, panic, and potentially double back to look for you, thinking you’ve crashed.

- The Rule: Never leave the sight of the group. If you need to stop, signal the rider behind you and the Sweep. The Sweep will stop with you while the rest of the group moves to a safe regrouping point.

3. Weaving and Position Swapping

- The Danger: Treating the formation like a highway slalom disturbs the “space cushion” of other riders. It forces everyone behind you to constantly adjust their throttle, leading to fatigue and “brake-tapping” throughout the line.

- The Rule: Pick your line and hold it. Consistency is the highest form of respect you can show your fellow riders.

4. Stunts and Aggressive Revving

- The Danger: Popping wheelies or aggressive “rev-bombing” in a tight pack can startle other riders—especially beginners—leading to panic reactions. In high altitudes, aggressive revving also puts unnecessary strain on an already oxygen-starved engine.

- The Rule: Save the theatrics for the track. On a Ladakh tour, the landscape is the star of the show, not your exhaust note.

The “Maturity Check”

True “expert” riders in Ladakh are identified by their smoothness, not their speed. A veteran rider knows that getting a group of ten people safely over a 17,000ft pass requires a collective effort. If you feel the urge to race or ride aggressively, Ladakh’s technical off-road sections will provide plenty of challenges—but do it when the group has officially disbanded for “free riding” periods, never while in formation.

8. Respect the Buffer: Eliminating the Tailgate

In the unpredictable terrain of the Himalayas, space is your best insurance policy. Crowding the rider ahead (tailgating) is the leading cause of “chain-reaction” accidents in group tours. Maintaining a disciplined gap isn’t just about courtesy; it’s about ensuring you have the time and tarmac necessary to react when the unexpected happens.

The Science of the “Safety Cushion”

When you ride too close to the bike in front, you lose your ability to see the road surface—potholes, black ice, or gravel patches are hidden until they are right under your wheels.

1. The 2-Second Rule (The Minimum Standard)

In a Staggered Formation, you should maintain at least a 2-second gap between you and the rider directly in front of you in your specific lane-third.

- How to measure: Watch the rider ahead pass a fixed object (like a milestone or a rock). Count “One-thousand-one, one-thousand-two.” If you pass that same object before you finish counting, you are too close.

2. When to Expand the Gap (The 4-Second Rule)

In Ladakh, “ideal” conditions are rare. Increase your following distance significantly in these scenarios:

- Dusty Trails: High-altitude dust (“fesh-fesh”) can hang in the air, reducing visibility to near zero. Give the dust cloud time to settle.

- Wet Roads / Water Crossings: Braking distances double on wet tarmac or muddy riverbanks.

- Steep Descents: Gravity adds to your stopping distance. If the rider ahead stalls their engine on a steep downhill, you need room to swerve or stop without sliding into them.

The Danger of the “Chain Collision”

If the Lead rider hits a sudden obstacle (like a stray Himalayan marmot or a fallen rock) and everyone is tailgating, the result is a concertina crash. Because bikes are staggered, a single mistake by one rider can knock down multiple teammates like a row of dominos.

9. Synchronized Stops: Fueling as a Unit

In the vastness of the Himalayas, momentum is your best friend. Breaking the group’s rhythm for individual needs causes “logistical creep,” where a 10-minute stop turns into an hour of lost daylight. To ensure you reach your destination before the treacherous mountain temperatures drop at sunset, the group must operate on a “One Stop, All Stop” policy.

The Blueprint for Efficient Logistics

By 2026, experienced touring groups follow a strict protocol for stops to avoid the “herding cats” scenario:

1. The Unified Fuel Stop

- The Rule: If one bike needs fuel, everyone tops up. * The Reason: You might have half a tank left, but if the next petrol pump is 150 km away and you skip this stop, the entire group will eventually have to stop again just for you. Collective fueling ensures the whole pack has the same range at all times.

2. Scheduled “Bio-Breaks” & Meals

- The Plan: Agree on these during the pre-ride briefing (e.g., “We stop every 90 minutes for 10 minutes”).

- The Protocol: Use these stops for everything—restrooms, checking luggage bungee cords, and hydrating. This prevents individual riders from peeling off every 20 minutes for a “quick photo” or a water break.

3. The “Designated” Photo Op

- The Reality: Ladakh is breathtaking, and you’ll want to stop every kilometer. However, stopping on narrow mountain passes or blind curves is dangerous.

- The Solution: The Lead Rider (Road Captain) should identify safe, wide “scenic pull-outs” where the entire group can park safely off the road. If you see something beautiful, wait for the designated stop rather than stopping solo.

10. The Golden Rule: Skill-Level Empathy

In the high Himalayas, ego is your greatest liability. A successful expedition isn’t defined by the fastest rider’s speed, but by the entire group’s safety. Respecting varying skill levels—especially in high-stress environments like water crossings or steep switchbacks—is what separates a professional touring team from a group of amateurs.

Cultivating a Supportive Pack Culture

The mountains can be intimidating. A rider who feels pressured is a rider who makes mistakes. Follow these guidelines to ensure everyone feels confident:

- Strategic Positioning for Beginners: Never leave a novice or slower rider at the absolute back (the “tail”). The rear of the pack often experiences the “slingshot effect,” requiring riders to accelerate aggressively to keep up.

- The Standard: Place less experienced riders in the #2 or #3 spot, directly behind the Lead. This allows the Road Captain to set a pace they can handle and provides them with a steady, experienced “line” to follow.

- Eliminate Peer Pressure: If the group decides to take a technical “off-road” shortcut or cross a rising nalla (stream), always provide an alternative. Never mock or pressure a teammate into a maneuver that exceeds their comfort zone.

- The “Slowest Rider” Benchmark: The Lead must constantly check their mirrors. If the gap between the middle and the rear is widening, the Lead must slow down. The group’s pace should be dictated by the rider with the least experience, not the most.

Bonus Tips:

- Keep your headlights on low beam—don’t blind the rider ahead.

- Always check your mirrors—not just for traffic but for group members.

- Hydrate often—especially in summer or mountain rides.

- Avoid loud music or distractions in your helmet.

Final Words

Group riding is more than just hitting the road together—it’s a team sport. It thrives on communication, respect, and rhythm. As a beginner, adopting good etiquette not only keeps you and others safe but also earns you credibility within the riding community.

So gear up, sync up, and enjoy the brotherhood (or sisterhood) of the ride.